For the next week, the eyes of the motorsport world will be on the rolling hills of Styria as for the first time in its history, two rounds of a Formula One World Championship season will be held at the same venue. But the circuit in Spielberg – which has gone by the names of the Österreichring, the A1-Ring and latterly the Red-Bull-Ring during its long history – has been the scene of many other landmark moments in F1 history since it held its first championship race back in 1970.

In its first form, the Österreichring was arguably the most spectacular and challenging circuit on the calendar for over a decade, between the end of top line racing at the 14-mile Nürburgring after Niki Lauda’s fiery accident in 1976 and the axing of the Austrian Grand Prix ahead of the 1988 season. Set in a scenic Styrian valley, the rises and falls of the circuit made for some of the biggest elevation changes on the calendar, with crests where the cars would nearly lift off, plunging high-speed sweeping corners to test the nascent aerodynamics, and small run-off areas bounded by grass banks or flimsy metal crash barriers. With no margin for error, the consequences of a mistake by the driver were potentially enormous. If it was still around in its original form today, the circuit would undoubtedly be obscenely fast, almost certainly nearly flat out for most of its length, and create so much dirty air that even DRS would struggle to cut through.

But in the days before F1 developed its overtaking fetish, its annual visit to the Österreichring was always a highlight. Due to its unique nature, it often threw up surprise results. Jo Siffert, from over the border in Switzerland, took his second and final world championship win there in a BRM in 1971. In 1975, a rain storm cut the race short, handing victory to March’s Vittorio Brambilla for the only time in his career. A year later, John Watson took his maiden win driving for the legendary American Penske team, almost a year to the day after they had lost their driver Mark Donohue after an accident at the circuit. Alan Jones won in a wet-dry race in 1977 for Shadow, another American-owned team, while in 1980 and 1981, there were wins for French drivers in French cars, with Jean-Pierre Jabouille’s second and final win for Renault being followed by success for Jacques Laffite of Ligier.

The most successful team at the Österreichring was Lotus, who had won there in 1972 with Emerson Fittipaldi and in 1973 and 1978 with Ronnie Peterson. But after dominating much of the 1960s and 1970s with revolutionary car designs from team founder Colin Chapman, the team had found themselves slipping behind their rivals. Though 1978 had been a hugely successful year, by the time of their visit to Spielberg in 1982, they had only won one race since their success in Austria that year: a win for Mario Andretti at Zandvoort in the following race. One race later, Peterson was killed in a first-lap crash at Monza, and while Andretti and Lotus clinched the drivers’ and constructors’ titles, the team had gone on to accumulate a 59-race winless streak, the longest in their F1 history up to that point.

There were several reasons behind this slump. Chapman’s innovative designs had once consistently kept them at the head of the field, including the exploitation of ground effect with the Lotus 78 and 79 which had helped the team to the 1978 titles. But once other teams had caught up, Chapman found himself unable to come up with more innovations to keep Lotus at the head of the field. From winning eight of the sixteen races in 1978, they won none in 1979 and finished a disappointing fourth in the constructors’ championship. A year later, they had slipped to fifth, with only one podium finish all year.

With the situation looking desperate by 1981, Chapman unveiled what he thought would be the team’s next great innovation. The Lotus 88 was a twin-chassis car: both chassis were sprung independently, allowing the outer chassis to stick to the road and massively increase the ground effect. However, while Chapman proudly demonstrated the car on television, Lotus’ rival teams were less impressed and lobbied for the car to be banned. While the car saw action in three practice sessions, the FIA blocked it from taking part in a race. By the end of the season, Lotus had dropped even further to seventh, their joint-worst ever season.

But it wasn’t just about the design work itself. Having blamed the team for Peterson’s death, Chapman became increasingly distant from the technical side of running the team. Instead, he found himself drawn more towards the business side, in a bid to try and find new revenue streams. In 1979, Lotus agreed a lucrative sponsorship deal with Essex Petroleum, owned by the extravagant American oil trader David Thieme. Chapman found Thieme fascinating, and was all too grateful to receive the funding. By 1980, the Lotus cars were decked out in a distinctive blue, silver and red livery bearing the Essex name. But when Thieme was arrested in April 1981, his oil empire collapsed, Lotus’ income disappeared, and the Essex name swiftly disappeared from the cars.

But it wasn’t just in F1 that Chapman was scheming behind the scenes to try and make more money. Lotus Cars was struggling to turn a profit, with particular problems in North America. To counter this, under Chapman’s direction it had become involved in the development of the DMC DeLorean sportscar in 1978. The project was part-funded by the British government, who supported the construction of the car as a job-creation exercise in Belfast, with a new factory and test track built in Dunmurry. However, by 1982, it became increasingly clear the project was collapsing, with disastrous sales figures and the closure of the factory just a year after opening, and questions were being asked as to why millions of pounds of government money had been wasted. Amidst investigations into the affair after DMC’s collapse, it would later emerge that they paid for Lotus’ work via an offshore company based in Switzerland called GPD. With Lotus shareholders not being informed of the deal, it amounted to serious fraud.

Chapman was a changed man. F1’s straight-talking envelope-pushing design genius had had his head turned by wealth and glamour, and was now applying his bending of the rules to more than just building racing cars. He was living an increasingly extravagant lifestyle fuelled by prescription drugs, and slowly drifting away from running his team. The brilliant Channel 4 documentary The Secret Life of Colin Chapman, one of the best ever made about F1, details Chapman’s decline, including interviews with his former senior colleagues at Lotus painting a picture of the sad final years of a man who did so much to change the sport.

Lotus arrived in Austria in 1982 fifth in the championship, after another disappointing season. But this was just one small subplot what had become one of F1’s most captivating years, with incredibly competitive and dramatic races, political turmoil, and three catastrophic incidents for the sport.

Ferrari had rewarded Gilles Villeneuve and Didier Pironi with the best car, the Harvey Postlethwaite-designed 126C2, which straddled the line between ultimate pace and reliability that other teams struggled with. But alas, the aerodynamics of the car were also fatally flawed – Villeneuve died in a violent accident at Zolder in Belgium, where the car took off after clipping Jochen Mass’ March, while Pironi had suffered what would prove to be career-ending leg injuries in a similar crash at Hockenheim. Villeneuve’s replacement Patrick Tambay, whose F1 career had been resurrected by the opportunity, had taken an emotional win in the German Grand Prix to put Ferrari seven points clear in the constructors’ championship, but his would be the only scarlet machine entered in Austria.

Tambay had been one of eight race winners in the first 12 rounds of the championship. The result was a close and competitive battle for the drivers’ title. Pironi led on 39 points, but his injuries ruled him out of racing, meaning his only chance of becoming France’s first F1 champion was if his rivals failed to score more than a handful of points in the last four races – seemingly a long shot, although with the way the season had already panned out, it wasn’t out of the question.

Even before his horrific crash, caused by a high-speed collision with Alain Prost’s Renault in practice, Pironi had already endured a tragic season. This had begun with losing his team mate shortly after a dispute over the ending of the San Marino Grand Prix, in which Pironi had passed Villeneuve on the last lap, breaking team orders. The pair never spoke to each other again prior to the Canadian’s death, something Pironi deeply regretted. Just three races later, he’d be tied to tragedy again – after stalling on the front row at Montreal, his car was struck by the Osella of Riccardo Paletti, who died from his injuries as a result.

While F1 was not a stranger to death in recent years, the combined loss of the championship’s most naturally gifted driver and one of its young talents within weeks of each other, in such public circumstances, was very difficult to take. Add in the injuries suffered by the championship leader, on the brink of establishing himself as one of F1’s biggest stars, and it made for a dark atmosphere in the sport. Moves were already being made to change the cars for 1983 to make them slower and safer, by removing the skirts that generated ground effect. It would be another 12 years before a driver was killed during a race weekend.

With Pironi recuperating, it was expected the title fight would be between the four drivers lying behind him in the standings. Leading the way was McLaren’s John Watson, who had taken spectacular wins at Zolder and on the streets of Detroit by surging through the field, and now lay nine points behind Pironi’s total. The McLaren MP4/1, designed by John Barnard and powered by the Ford Cosworth DFV engine, was F1’s first carbon fibre chassis and had proven its worth since its introduction in 1981, becoming the fastest normally-aspirated car in the field.

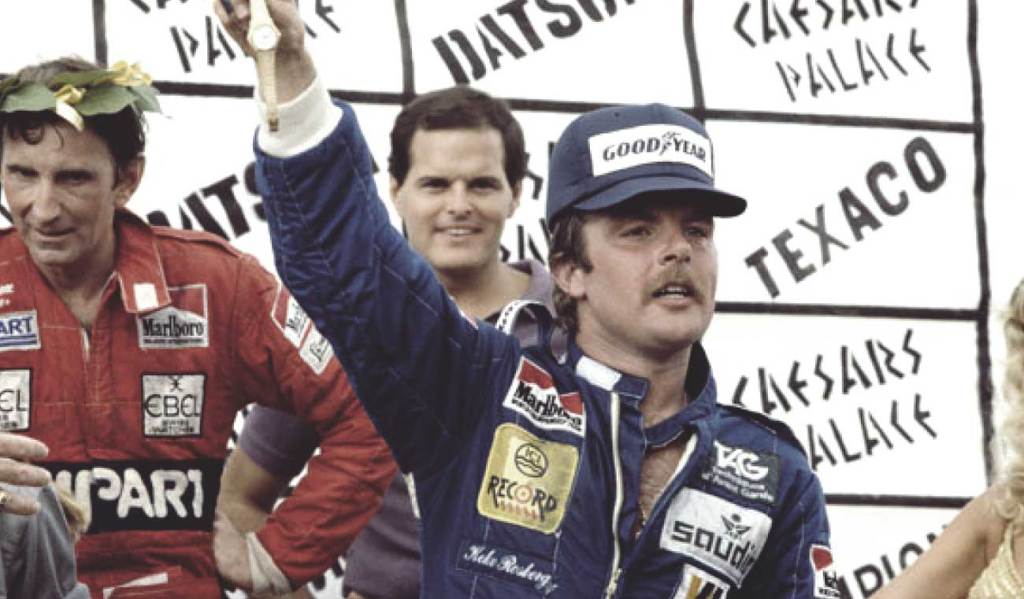

Three points further back was Williams’ Keke Rosberg, who had inherited Carlos Reutemann’s mantle as team leader after the Argentine driver, who had finished runner-up in 1981, had abruptly quit F1 after the first race of the season. Rosberg was yet to win a race, but in this topsy-turvey campaign, he had quietly accumulated points with consistent driving in the brand new FW08, a Cosworth DFV-powered car that couldn’t match the turbos for pace but was far more reliable.

In fourth place, 14 points behind Pironi, was Prost. The Frenchman, in his third season of F1, had begun the year in great form, winning at altitude at Kyalami where the turbos were at their best, and then inheriting a win in the second race at the Jacarepaguá circuit in Rio de Janeiro after Brabham’s Nelson Piquet and Rosberg were disqualified. But despite starting with 18 points from the first two races, he failed to score from the next seven races as unreliability dogged the rapid turbo-powered Renaults – although in Monaco, he lost a win through a costly rare driving error with a handful of laps to go. Second place in his home race at Paul Ricard had brought him back into contention, though, and if the Renaults held together, he still had a strong chance of winning the championship.

The other contender, a point behind Prost and 15 points behind Pironi, was McLaren’s Niki Lauda. Twice world champion at Ferrari in 1975 and 1977, Lauda was in his first season back in F1 after quitting at the end of 1979. In just his second race back on the streets of Long Beach, he had won convincingly, proving he had lost none of his speed and race management skills. One of the most intelligent drivers ever to grace a racing circuit, Lauda was always a threat and was the only driver in contention for the championship who had already won it. Added to that, the Austrian Grand Prix was his home race – an event he had never won, but one in which his fans were desperate for him to perform well.

The other race winners this year were Prost’s Renault team mate René Arnoux, another victim of poor reliability from the turbo engines, and the Brabham pair of Riccardo Patrese and 1981 world champion Nelson Piquet. Brabham had endured a frustrating 1982 season, as they transitioned from normally-aspirated Cosworth DFV engines to turbocharged BMW engines. They had suffered bad luck on numerous occasions, with Piquet in particular bearing the brunt of the issues. He was disqualified from a home win in Rio for the car’s water-cooled braking system, inexplicably failed to qualify in Detroit due to BMW engine problems, and was then taken out of the race lead at Hockenheim by backmarker Eliseo Salazar in his ATS – leading to one of the most famous scenes in F1 history, as Piquet attacked Salazar on the side of the track.

However, Patrese had been fortunate to win a thrilling Monaco Grand Prix despite spinning late in the race, and Piquet had won in Montreal to give BMW its first F1 win. But the team had effectively written off the rest of the season, and were now experimenting with race strategy, as they looked to do the first refuelling stop in F1 since the 1950s. Unreliability and incidents in previous races had preventing it from happening so far, so as F1 headed to Austria, excitement was building for the big moment.

But the field was more than just being about the stars at the front. In all, 29 cars were entered for the Austrian Grand Prix, with only 26 to qualify for the race. These included potential front-runners like the big-budget Alfa Romeo team, yet to win since their return to F1; the legendary Tyrrell team, who had dominated F1 with Jackie Stewart in the early 1970s but had failed to win a race since 1978; and Ligier, who had been major contenders in previous seasons but had little to show for 1982, through to a stack of smaller teams: Arrows, Ensign, Toleman, ATS, Osella, Fittipaldi and RAM March. A raft of drivers were jostling around the various different seats as money changed hands and sponsors called the shots, with entry lists changing race by race. 39 drivers would feature in at least one race weekend in 1982, with seven appearing for more than one team – if you were an F1 aficionado who loved obscure backmarker drivers, this was a golden age.

And that was before you get to the five different tyre suppliers, the seven different engines, and 15 other circuits on the calendar, each with their own unique stories to tell – this was a deep and fascinating sport, grappling with the move into the new world of global television coverage, manufacturer involvement and multi-million dollar sponsorship deals.

However, ultimately the basic principle of F1 was unchanged: it was still about how fast you could go. In 1982, the fastest cars were the turbo-powered Ferraris, Renaults and Brabham-BMWs, and this advantage only increased at high altitude circuits like the Österreichring. Piquet put his Brabham on pole position, just under fourth tenths faster than Patrese and over a second faster than the fastest non-Brabham, the Renault of Prost. Tambay was fourth in the only Ferrari, ahead of Arnoux. The fastest normally-aspirated car was Rosberg’s Williams in sixth, ahead of De Angelis in the lead Lotus, Tyrrell’s Michele Alboreto, Derek Daly in the second Williams, and home hero Lauda in the first of the McLarens – the top 10 was covered by a massive 4.5 seconds!

Team mate Watson, in his new role as de facto championship leader, struggled to line up 18th, 6.5 seconds behind Piquet. The final qualifier, a full 7.4 seconds behind the pole-sitter, was Ireland’s Tommy Byrne of Theodore, the first time he had made the field since stepping into the small team for the German Grand Prix. He pipped March’s Raul Boesel by less than two tenths, with Osella’s Jean-Pierre Jarier and Hockenheim villain Salazar in the ATS also failing to make the field.

The start of the race at the old Österreichring was always a major hazard, as the start-finish straight was very narrow and unusually bounded by a crash barrier tight to the track on the far side. This created numerous first lap incidents, and 1982 was no exception. As Piquet led the field on the climb up to the Hella-Licht chicane, the two Alfa Romeos of Andrea de Cesaris and Bruno Giacomelli tangled with Daly just a few yards into the race, eliminating all three cars and sending debris across the track.

At the front, Prost outmanoeuvred Patrese to take second, but the Italian soon re-passed the Renault on the run up to the Dr Tiroch Kurve. When the field came around at the end of the first lap, the Brabhams led Prost, Tambay, Arnoux, De Angelis, Rosberg and Alboreto.

However, this would immediately change dramatically. That debris that littered the circuit after the first-lap crash had not been fully cleared, and Tambay soon suffered the consequences, with his right rear tyre blowing, leaving him to tour around slowly to the pits for almost an entire lap. Soon after, Alboreto, who was fighting with Rosberg for sixth, crashed heavily into the barriers at the Bosch Kurve, but despite the obvious mess left by his car over the track, the race was again allowed to continue. Rosberg soon slid back, being passed by the Lotus of Nigel Mansell, and the fast-started turbo-powered Tolemans of Derek Warwick and Teo Fabi. Warwick, who had briefly ran as high as second in the British Grand Prix in the cumbersome car, soon passed Mansell for sixth, but on the eighth lap, his suspension broke and Fabi’s transmission failed, taking both Tolemans out of the race.

Patrese quickly breezed past Piquet, and the two Brabhams disappeared up the road, leaving Prost behind at a rate of over a second a lap. Their aggressive strategy of half-tanks of fuel and softer tyres looked to be paying off, as they seemed to be creating the ideal gap for their pit stop. The pace was too much for Arnoux’s Renault, which headed for the pits on lap 17 with engine trouble while the Frenchman was lying in fourth, eliminating another of the major turbo contenders. But a lap later, Piquet was also in the pit lane – his soft tyres had blistered, and he required an early pit stop, several laps ahead of schedule, dropping him to fourth between De Angelis and the recovering Rosberg. It was something of a damp squib for the first fuel-and-tyre stop in modern F1 history, and left the reigning world champion with a lot of work to do to claim victory.

Patrese was able to continue at the front, pulling out a lead of over half a minute over Prost ahead of his own pit stop on lap 24. The extra six laps gave him enough of a cushion to rejoin ahead of the Renault, but without the tyre blanket technology of today, he exited the pits on cold tyres, allowing Prost to close in. Then, on lap 28, bang! Patrese’s engine blew on the approach to the Texaco Schikane, the double left-hander in the middle of the circuit. The failure sent the Brabham into a high-speed spin, and the car careered into a grass bank only a short distance from where a photographer had breached the spectator barrier. Thankfully, no one was injured, but Patrese’s chance of a second win of the season was gone.

Prost now led by nearly half a minute, and with Watson struggling way down the field, it seemed he was on the verge of launching himself back into championship contention. De Angelis held a comfortable margin over Piquet, who was soon confined to the sidelines himself when the camshaft failed. The Brazilian’s retirement released Rosberg, now up to third, ahead of 1981 winner Laffite in the Ligier, his best run of the season so far. British driver Brian Henton was enjoying his best performance in F1, slowly working his way up to an impressive fifth place, only for his engine to fail just a lap after Piquet retired. It was proving to be a race of attrition at the most demanding circuit on the calendar: with “Superhen” gone and other drivers further down the field dropping out, there were only nine cars left in the field with 20 laps to go.

Prost continued to steadily increase his lead out to over 36 seconds, and seemed almost certain to win, until on lap 49, with just four laps to go, flames started to flicker from the exhausts of the Renault engine. The car ground to a halt, and De Angelis swooped by to take the lead for the first time in his F1 career. A quietly impressive performance from the Roman had left Lotus, after all the turmoil they had faced, on the brink of their first win in nearly four years. But there was just one more challenge to face off.

Rosberg had been steadily closing on De Angelis for several laps, whittling the gap down to around four seconds as Prost pulled over to retire. It seems the Williams had protected its tyres better, and the Finn was now using all his skill to wrestle the car around the high-speed sweeps. In a wonderful display of attacking driving, with the car drifting sideways through every corner, Rosberg closed dramatically. With two laps to go, the Lotus was clearly in his sights, around two seconds ahead. At the start of the final lap, the gap was down to 1.64 seconds – it seemed a lot to make up, but De Angelis seemed to be struggling for grip and the engine coughing for air, while Keke was now clearly in an untouchable zone. With no dirty air to disturb the car’s aerodynamics, he continued to close.

Going into the last corner, De Angelis was forced to take a very tight defensive line on the side, while Rosberg drove a wider line to try and cut back inside as De Angelis drifted across the circuit. Rosberg took as much tow as he dared, before moving out of it to pull alongside. However, at the final moment, the car stopped gaining. De Angelis held on to win by just 0.05 seconds: at the time, it was the second-closest grand prix finish in history. Colin Chapman was there at the finish, performing his traditional cap-toss as his car crossed the line to win.

De Angelis celebrated with both arms aloft, lifting the visor on his distinctive stormtrooper-style Simpson Bandit helmet. It was a first win for him, a 72nd win for Lotus, and a remarkable 150th win for the Ford Cosworth DFV engine, which had powered an unlikely winning car. Rosberg, though disappointed to miss out on his first F1 win, collected six valuable points to leave him second in the championship, now only six points behind Pironi’s total. The remaining runners were all a lap adrift: perhaps the most remarkable story was that of Tambay, who drove brilliantly to finish fourth despite his disruptive early puncture, ahead of Lauda who struggled the entire race to finish a disappointing fifth. Just seven of the 26 starters finished the race, with Prost and John Watson classified finishers despite not running at the end.

In the event, this race would prove crucial in the drivers’ title fight. Rosberg would eventually claim his maiden win in the next race, the Swiss Grand Prix at the French circuit of Dijon-Prenois; while he made himself unpopular with the locals for passing Prost late on to take the victory, it would take him beyond Pironi’s total, and with Watson enduring a difficult end to the season, he calmly cruised to the championship in the remaining rounds, finally claiming it with a fifth-place finish in the season finale in Las Vegas. While there was no question he had benefited from an extreme set of circumstances, he nonetheless deserved the finest honour in the sport having driven brilliantly all year in his first season in a competitive car, and he would go on to enjoy a stellar career.

For Lotus, though, 1982 would prove to be the end of an era. Despite the hope provided by the win in Austria, the team would collect just one point in the final three races. But that was nothing to compare with what was to follow. Shortly after the end of the season, on 16th December, Colin Chapman died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 54, shortly after returning from a test session. The news rocked the sport of F1 and Lotus, both of which had lost a great leader and innovator.

While Lotus would live on after his death, it never regained its status as one of the leading teams in F1. The test Chapman was returning from shortly before his death was part of the development of the first F1 car with active ride suspension, his last great innovation, but his death meant it would be another four years before it appeared on a Lotus car in a race, and would never be fully realised by the team. The team would go on to win seven races with Renault and Honda turbo engines under the stewardship of Chapman’s successor Peter Warr – a second win for De Angelis, and six for a young Ayrton Senna – but by the late 1980s, it was in steep decline, finally closing its doors in 1994. Just weeks before, Williams had won their third consecutive constructors’ title, the Didcot team having taken over from Lotus as one of the great powerhouses of F1.

While Lotus was clearly not the force it once was in 1982, it remains the final act for one of F1’s greatest figures – the 72nd and last win of Chapman’s career. But with that dramatic finish, what a way to bow out!