Poor Valtteri Bottas. F1’s latest Flying Finn is yet to grab the affections of the racing public, by virtue of being beaten narrowly week in week out by one of the greatest drivers of all-time. It’s a thankless task, and for all that he’s not living up to the man he replaced in the Mercedes team, Nico Rosberg, in taking the fight to Lewis Hamilton on the track, he is doing a very solid job and is heading to his second runners-up spot in the world championship.

So how does Valtteri stack up against the other runners-up in F1 drivers’ championship history? Well, finishing as the runner-up twice is a pretty remarkable achievement – 17 other drivers have achieved this in F1 history, including the likes of Ayrton Senna, Alain Prost, Michael Schumacher and Hamilton, but only four have failed to win a title themselves. So to understand further just how good he is, I’ve looked at the last 14 drivers to finish second in the standings, over the past 50 years – I’ve avoided including José Froilán González, Stirling Moss, Tony Brooks, Bruce McLaren and Wolfgang von Trips simply because it’s difficult to compare drivers from an era of very few races, few genuinely competitive cars and little television footage with those, like Bottas, who have their every lap scrutinised. That being said, Moss would clearly be ranked at number 1 otherwise, because he’s the obvious choice.

14) Heinz-Harald Frentzen (1997)

This is more of a technicality. Heinz-Harald was no disgrace as a driver – this was, after all, the man who took the fight to McLaren and Ferrari in a Jordan in one of the most remarkable under-the-radar championship campaigns of all time. If he’d finished second driving one of the yellow cars, he would have been ranked much higher. However, he’s effectively in the record books by default here, for finishing runner-up in the 1997 season despite actually finishing third – he was promoted to second place after the actual runner-up, Michael Schumacher, received F1’s greatest non-punishment: disqualification from second place in the championship after his collision with Jacques Villeneuve in the European Grand Prix at Jerez.

Frentzen’s 1997 campaign amounted one win – the San Marino Grand Prix – in a car that was by far the fastest in the field to begin the year, as well as various collisions and poor performances. He could have won a second in Hungary, but for a fuel leak which caused a fire. But too often he was found wanting when Villeneuve was off the boil or needed a wingman. He finished some 39 points behind his team mate, which was a heck of a lot in the days of 10 points for a win and 17 races. Despite his one-off title charge in 1999, his career was one of unfulfilled potential, and it’s hard to justify putting him anywhere other than last on this list.

13) Riccardo Patrese (1992)

Like Frentzen, Patrese had better seasons than his actual runner-up campaign. Like Frentzen, he was blown away by his team mate at Williams and ended up a long way behind. Like Frentzen, he probably should have won the Hungarian Grand Prix that year. Patrese engaged in a challenging scrap for second place in 1992, as the field trailed in Nigel Mansell’s dust. Despite the dominance of the team’s FW14B, the Italian struggled to adapt to its active ride suspension. In the end, it was his fortunate win at Suzuka in the penultimate round, in a race where Mansell, Schumacher and Senna all retired, that took him clear in the battle for the runners-up spot. After being denied a second consecutive win with problems in Adelaide, he finished the year a massive 52 points behind Nigel.

Prior to the emergence of active ride, Patrese had actually been quite close to Mansell in performance. In 1991 he took a particularly impressive win in Mexico and followed it up with another in Portugal. But despite his long career, six race wins and eight pole positions, he was never really a title contender in any meaningful sense. His early career was characterised by great speed and inconsistent race performances, and he was significantly outperformed at Brabham by Nelson Piquet. After several years in the midfield, he found himself in the right place at the right time to relaunch his career with Williams, becoming a more consistent driver but struggling to hit the heights of the great talents around him. As a result, it’s hard to rank him above drivers who had a genuine shot at the title.

12) Michele Alboreto (1985)

Alboreto remains one of the forgotten championship contenders in F1 history. His 1985 campaign could so easily have ended very differently, as he proved to be a match for Prost in the first half of the season and led the standings by five points after nine of the 16 races. However, he failed to score in all of the last five races to leave him well behind the McLaren driver in the end, and the story of his hopes going up in Italian smoke now gets lost in the overall narrative of Prost’s onward march towards record-breaking glory.

Michele’s F1 career sadly never recovered from this. Despite having been a major prospect following his two race wins for Tyrrell in 1982 and 1983, Ferrari only had one strong seasons in his five with the team. By the time it was back on an upward trajectory, he had been supplanted as the team’s lead driver by Gerhard Berger, and was soon replaced altogether by Mansell. A disastrous return to Tyrrell saw him fired mid-season, and he saw out the rest of his career in the midfield or lower. It was a sad end for a driver who might have been able to take Prost to the wire had Ferrari maintained reliability in 1985, although we’ll never get to find out how close he may have run him – for Alboreto, 1985 proved to be an anomaly, both for the team and his own performances, as he never reproduced the consistent high level of performance he had shown that year.

11) Clay Regazzoni (1974)

Eight drivers on this list achieved at least one of their runners-up spots with Ferrari, and five of them are largely inseparable. They also have a lot in common. Regazzoni, for one, had a late career renaissance at Williams in 1979, just as Felipe Massa would 35 years later, but his stand-out moments in F1 mostly came in the first half of the decade. Clay’s first part-season in F1 in 1970, in which he also juggled a title-winning European Formula Two campaign, was remarkable: in his first race at Zandvoort, he finished fourth; in his second race at Brands Hatch, he matched it; in his third at Hockenheim, he battled for the race win with Jochen Rindt and team mate Jacky Ickx before retiring; in his fourth at Spielberg, he finished second behind Ickx; in his fifth at Monza, he won, becoming a tifosi icon. Two further second-place finishes secured third in the championship, only 12 points behind posthumous champion Jochen Rindt, despite having missed five of the first six races.

Regazzoni quickly built a reputation as a tough, uncompromising racer – in an era of clean, gentlemanly racing, he was the one driver who consistently pushed the boundaries. But in terms of results, he proved to be Mr Consistency, particularly in 1974, where despite having spent 1973 away from Ferrari at BRM and being outpaced by new team mate Niki Lauda on his return, his seven podiums – including a win on the fearsome Nürburgring Nordschliefe – left him level on points in the lead with Emerson Fittipaldi going into the final race at Watkins Glen. Sadly, he suffered a disastrous weekend in New York state, qualifying a lowly ninth and finishing four laps down in 11th after struggling with an ill-handling car with a defective front damper. Fittipaldi finished fourth to take the title by three points. Thereafter, Lauda asserted his dominance in the team, with Clay cast into the supporting role, but he remained a consistent figure at the top end of the grid until being replaced in the team by Carlos Reutemann for 1977.

10) David Coulthard (2001)

Despite his long career at the highest level, including over a decade in top teams, just how good Coulthard was remains something of a puzzle. He was close in performance to Damon Hill at Williams in 1995, his first full season of F1, and wasn’t too far off Mika Häkkinen in his first two years at McLaren either. But his career never seemed to recover from those consecutive races where he was forced to let Häkkinen through to take the win, at Jerez in 1997 and in Melbourne in 1998. Opinion remains divided as to whether he would have struggled in any case, or if this damaged his confidence and strongly hinted at a wider issue in the team, but the result was Coulthard would never discover the consistency he needed, and would later find himself lacking the one-lap pace to compete with the very best.

Coulthard’s runner-up spot came in 2001, when he began as Schumacher’s main contender by winning two of the first six races and generally outperforming Häkkinen. However, Coulthard and McLaren’s form soon dropped away, as he failed to win a race for the rest of the season – his consistent podium finishes were no match for an increasingly dominant Schumacher. In the end, he finished 58 points behind the Ferrari driver. But in reality, the closest DC came to the title was in 1999, when he clawed his way back into contention after a typically inconsistent start to lie 12 points behind Häkkinen and Eddie Irvine with three races to go. His hand was further improved during the European Grand Prix at the Nürburgring, when Häkkinen and Irvine were both way down the field after poor decisions to pit for wet tyres, Frentzen retired, and Coulthard found himself in the lead. He was on the cusp of being just two points from the lead with two races to go when he slid off the road into the tyres, effectively ending any hopes he had of becoming champion. He would never get another chance like it, cementing his reputation as Britain’s nearly man. Whether he could have won the 1996 title if he had stayed at Williams is another matter for debate…

9) Eddie Irvine (1999)

As much as Coulthard became a figure of fun in the early 2000s with his claims that “this year will be my year”, I imagine a lot of people are getting the pitchforks out right now because I’m ranking Irvine higher than him. But hear me out – Irvine got much closer to a championship than Coulthard ever did, and was criminally underrated throughout his career. After a stint at Jordan that saw him surrounded in controversy and quietly match the highly-rated Rubens Barrichello in one-lap pace, Irvine found himself as Michael Schumacher’s number two at Ferrari, a role that suited him well. Like Martin Brundle at Benetton before him, Irvine chose to concentrate on his own performance rather than trying to match the greatest driver of the day, and eventually it would reap its rewards. A first win came in 1999, and through consistent performances, he was in a strong position to pick up a title challenge for Ferrari when Schumacher was injured at Silverstone.

Despite Ferrari switching development to the 2000 car as soon as the German was out of the picture, Irvine won three more races – albeit one gifted by the returning Schumacher in Malaysia – to lead the championship by four points going into the final round at Suzuka, a track he knew well from his days racing in Japan and where he always performed well. However, after a crash in qualifying, he was off key all weekend and ended up losing out by two points. His career after this with Jaguar never lived up to this, but for one brief moment, Irvine did look like a world-class driver in the making. In the circumstances of the time, there are a number of better drivers who would have won the championship in his position, and he slightly lacked the consistency to punish the McLaren drivers for some of their errors. But whether they would have been resilient enough to have coped with three years before this of being beaten by Schumacher every other week is another matter…

8) Felipe Massa (2008)

It was a genuinely tough call as to whether I’d go for Irvine or Massa in this position. In some ways, they had very similar results. Both inherited their lead driver role at Ferrari in their strongest seasons, but for very different reasons, and both would have won the championship had the cards fallen slightly differently. Both struggled to live up to their billing as a nearly-champion, but in very different environments – Irvine at a political Jaguar team, Massa at a Ferrari team that came to be dominated by Fernando Alonso. But both are polar opposites as personalities and drivers.

Massa had shown flashes of speed in his days at Sauber, but it wasn’t until his second season at Ferrari in 2007 that he fully blossomed into a leading driver. But for bad luck in the second part of the season, he may well have ended up in the mix for the championship in the closing rounds, but in the end he was forced to play a supporting role to eventual champion Kimi Räikkönen. The following year, with Räikkönen struggling for form mid-season, Massa became Ferrari’s best chance of winning the championship. But for the fuel hose shenanigans, the collision with Hamilton at Fuji and the dramatic events of the last lap at Interlagos, he may well have won it. He again matched Räikkönen in early 2009, proving it had been no fluke – but was this the sign of a Räikkönen who was already losing his edge in F1? Many put his poor performances alongside Alonso in the years after down to his head injury sustained in Hungary that year, but in all likelihood, based on his performances before and after, he was probably just a good driver coming up against a great one. On his day, he was fast – he just didn’t have the consistency to become an elite level driver.

7) Valtteri Bottas (2019)

Yep, more pitchforks outside my front door. But take a step back – what Bottas is achieving at Mercedes at the moment is actually genuinely impressive. Sure, he’s not matching Lewis Hamilton. But there are very few drivers in F1 history – let alone on the current grid – who could do that. Even so, he’s still on course to finish second in the championship again, proving that if Lewis had been replaced by a distinctly average driver in the second car two years ago, Valtteri would most likely be a world champion – he is technically capable of achieving that. For all that we get frustrated, it’s still an impressive set of results viewed in isolation.

He may be driving for the sport’s most dominant team in its entire history, but in an incredibly competitive and talented grid, you still have to deliver – just look at how drivers like Alex Albon, Pierre Gasly and, heck, even Sebastian Vettel have struggled in top teams in the last couple of years. There may be better drivers on the grid than him, like Daniel Ricciardo, Charles Leclerc or Max Verstappen, but as long as he keeps finishing consistently on the podium and racking up the points, he’s earning his position in the team and demonstrating he’s a very fast and capable driver. Though the “Bottas 2.0” statement has been mocked, he has taken a step up in the last two seasons to become a much more consistent driver – and that automatically puts him ahead of several drivers in this list. He is definitely capable of winning the title – he just needs Lewis to retire and leave him have a crack at it, then we can see how good he really is.

6) Rubens Barrichello (2002, 2004)

Rubens’ characterisation as the classic number two driver doesn’t fully do his ability justice. He arrived at Ferrari in 2000 with a reputation as one of the most underrated drivers in the sport, having just enjoyed a strong third and final season at Stewart in which he’d taken a pole position and three podiums. He wasn’t quite regarded as highly as he had been five years before, where he had been seen as one of the next superstar drivers, but his ability as a future race-winning and potentially championship-winning driver wasn’t in doubt.

But after six years as team mate to one of the best drivers ever to have lived, in which he’d finished second in the championship twice and won nine races, he was seen in Brazil as a coward, a traitor and a disappointment for moving over for Schumacher in Austria in 2002, and elsewhere as “Twobens”, the man who was naïve enough to believe he was going to challenge Schumacher and was either never able to or never allowed to.

However, in reality he laid a lot of the ground work for Michael’s success with his technical skills and car development, and after four years in Brackley, he finally showed he was still a capable driver towards the end of 2009 when he worked his way back into title contention and pushed Jenson Button hard. His pole lap in torrential rain at Interlagos, that circuit he could never quite win at despite his home advantage, showed he never lost his natural talent – he just lacked the consistency and political skill to get a team around him to get over that final hurdle.

5) Carlos Reutemann (1981)

It’s a cliché, but Carlos’ ranking on this list really does depend on what mood he’s in on the day. Despite being 29 when he made his debut – a race he qualified for on pole at his home circuit, for what it’s worth – he enjoyed a decade-long career driving exclusively for some of the sport’s top teams: Brabham, Ferrari, Lotus and Williams. Even today, his 12 wins put him behind only Coulthard (13) and Moss (16) for the most victories without winning the championship.

While it is true to say Carlos lacked the ultimate consistency to join the greats of his era, his lack of world championship success came down to the fact that he was never in the right place at the right time. During his four-and-a-half years at Brabham, the team failed to produce a car capable of winning the championship. He joined Ferrari after Niki Lauda’s fiery crash in 1976, and could easily have gone on to become their team leader had he not fully recovered, but by 1977 Lauda was back to his best and Carlos fell into his shadow for two years. In 1979, he joined Lotus fresh from their dominant championship success of 1978, but the Lotus 79 quickly became outdated and the 80 was a disaster, although he still outperformed Mario Andretti.

But the biggest miss came in 1981, when he failed to win the title due to the South African Grand Prix – a race he won brilliantly – being made a non-championship event and a woeful performance in the season finale at Caesars Palace. He might have won in 1982 too had he not inexplicably retired after one round of the season, while driving the car that would take team mate Keke Rosberg to the title. Reutemann’s career is proof that the higher we get on the list, the more we get to the “coulda woulda shoulda” drivers – he remains the classic example.

4) Ronnie Peterson (1971, 1978)

Ronnie is perhaps more myth than legend these days, but anyone who has watched him race, even via archive footage, knows that he was a driver with a very special talent. It’s easy to characterise him as the wild one, with that famous and frequently-cited image of him going sideways through the old Woodcote corner at Silverstone in the Lotus 72, but Peterson’s failure to win the championship was much like Reutemann’s – right place, wrong time.

His breakout year at March marked him as a star of the future – in a year where no one could match the combination of Jackie Stewart and Tyrrell, Peterson finished second in the championship despite not winning a race, although he did finish second four times, including finishing just 0.01 of a second behind Peter Gethin at Monza – about as close as you get to winning in F1 history. And this was of course all while driving for the March team, who were by no means giants in F1 at the time. He got his move into the big time in 1973 with Lotus, but it took him until the second half of the season to hit his stride in the Lotus 72, by which time he was already out of contention.

But it was the failure of Lotus to develop an effective successor to the 72 that probably cost him his best years as a driver – he was still driving the 72 at the end of 1975, some five years after the car had been introduced, and he quickly lost patience, leaving for March after one round of 1976. When he returned in 1978, he found himself in a winning car as a contracted number-two to Mario Andretti, a driver who was perhaps less naturally-talented but more politically-adept. At 34, he should have been entering his peak as a driver and was already bound for McLaren when he tragically died at Monza. While it would have been a struggle initially, it’s a travesty that we never got to see his Indian summer in the Barnard-designed MP4/1.

3) Didier Pironi (1982)

Of all the drivers on this list, Pironi is the only one who completely deserved to win a world championship. The only reason he didn’t was sheer tragic bad luck, a fate that could have befallen just about any driver on the 1982 grid. For all that 1982 was “the season no one wanted to win”, Pironi had taken a hold of it after his second win of the year in the Dutch Grand Prix at Zandvoort. This, followed by podiums at Brands Hatch and Paul Ricard, had left him nine points clear – a full race win – ahead of the trip to Germany. With five races to go, sitting in the best car in the field, the Ferrari 126C2, he was well on his way to becoming France’s first world champion.

Then, in a wet practice session while driving at high speed through the famous Hockenheim forest, he suffered a horrifying accident with Prost’s Renault that left him with career-ending leg injuries. Despite missing the rest of the season – taking his total of missed races in 1982 to six of the 16 – he still finished as the runner-up, just five points behind champion Keke Rosberg. He tried to make a comeback several years later, but he found his route back into F1 blocked – reputedly by Prost, who it is claimed prevented McLaren signing Pironi for the 1987 season – and he took to powerboat racing instead, which tragically claimed his life in 1987.

For all that Pironi is regarded as the lesser of the two drivers that the 126C2 claimed the careers of in 1982, he was delivering – six podiums in 10 races is an impressive return, and there’s nothing to say he wouldn’t have picked up more in the remaining races but for his injuries. He had the speed and the steely, calculating mindset to see out the championship, and who knows where that would have taken him from there. In his absence, Ferrari won the constructors’ championship in 1982 and 1983, so there would undoubtedly have been more wins and maybe titles beyond this, but for that cruel stroke of luck at Hockenheim.

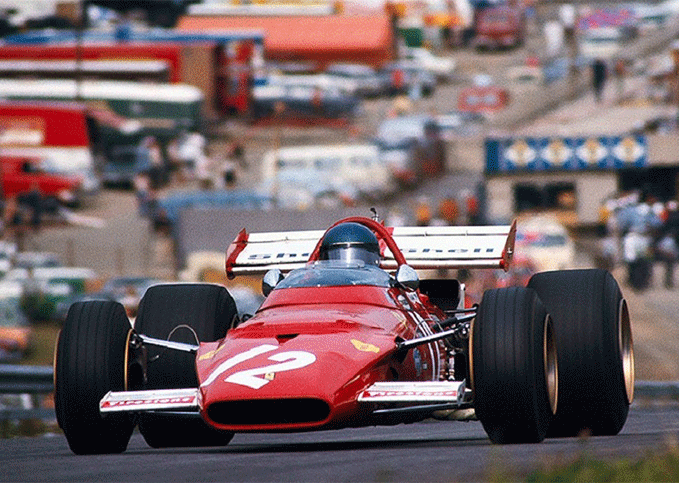

2) Jacky Ickx (1969, 1970)

There are few drivers in F1 history who failed to win a world championship but whose name careers the level of prestige you would associate with the champions. Ickx has to be one of those. For five years out of six between 1968 and 1973, he was Ferrari’s number one man, inheriting the mantle previously held by the likes of Ascari, Fangio, Hawthorn and Surtees – and all this having joined the team at just 23 years old, at a time when driving for a leading team in the sport at that age was relatively unheard of.

In that period, he won eight races, of which six were with the Scuderia – two came while driving for Brabham in 1969, his only year away from the team, when he finished as a distant runner-up to a dominant Jackie Stewart. The following year, he finished second again, this time to the late Jochen Rindt, with the Ickx-Ferrari package having emerged as the dominant one in F1 following the Austrian’s tragic death at Monza. But for a disappointing start to the season, in which he failed to score in the first four races and suffered burns in a crash in the Spanish Grand Prix at Jarama, he may well have taken the title.

While expectations were high going into 1971, Ferrari became an increasingly dysfunctional team and Ickx’s F1 career became one of its victims, with his acrimonious departure midway through 1973 effectively ending his days as one of the sport’s top drivers at the age of 28 and paving the way for the arrival of Niki Lauda. Thereafter, he bounced around the paddock – a stint at Lotus proved to be disappointing as the team struggled to build a replacement for the successful 72, and by the end of the decade, he was only making sporadic appearances, including deputising for Patrick Depailler at Ligier in a ground-effect car that he didn’t like driving. But this doesn’t do his ability justice – not only was he possibly the greatest sportscar driver of all time (sorry TK!) and a winner of the Paris-Dakar Rally and Can-Am Championship, but he was also one of the best of his generation in F1. His talent deserved more success at the highest level, and he remains a highly underrated driver.

1) Gilles Villeneuve (1979)

Maybe I’m succumbing to romance here, but to me there was only ever one choice for the top spot in this list. A sceptic would point to Gilles’ record in F1 as inconsistent and subject to occasional lapses that truly great drivers would never make. But to watch him in action, at the front of the field in cars that had no right to be there, showed what a talent F1 lost at Zolder in 1982. But he wasn’t just the guy who flung around average Ferraris without a care in the world – here was a driver who had developed into the sport’s leading driver, and was inevitably going to be champion in the right car. Much like Max Verstappen today, it was a question of “when” rather than “if”.

Villeneuve took around a season and a half to settle down in F1 following his debut in 1977, with his famous victory on home soil at the 1978 Canadian Grand Prix saving his Ferrari seat and possibly his career. In 1979, he was kept on to play a supporting role to Jody Scheckter, who had already proven himself an elite level driver at Tyrrell and Wolf and was the natural choice to lead the team. At the start of the season, the new ground-effect Ligier was superior to the Ferrari, with Jacques Laffite winning the opening two races of the year, but at Kyalami and Long Beach, Villeneuve won twice ahead of Scheckter to lead the championship – this wasn’t in the script. As Ligier slipped back and Patrick Depailler smashed his legs in a handgliding accident, it became clear the Ferrari drivers would be the main title contenders.

Scheckter would eventually hit back with wins at Zolder and Monaco, but it was more his consistent points finishes rather than out-and-out speed that won him the championship. He was also helped by an odd dropped-score system that split the championship into two halves, with the best four scores from each half counting – in the end, Villeneuve won at Watkins Glen to finish just four points behind Scheckter, although Scheckter had scored seven more points over the course of the season pre-dropped scores.

Scheckter won the title with two races to go with a Ferrari 1-2 at Monza, where Villeneuve, who had been fourth in the standings going into that race behind Laffite and Williams’ Alan Jones, dutifully followed him home as per team orders. Gilles had effectively lost the title in the middle of the season, and some of the wilder moments from the year are often cited as part of his legend – the thrilling battle with Renault’s René Arnoux over second place at Dijon, and the puncture and resulting damage at Zandvoort while battling Williams’ Alan Jones for the win. But in reality, this wasn’t typical Villeneuve – yes, he was a risk-taker both on and off the track, but he wasn’t utterly reckless; in 1979, he had simply suffered more bad luck, bearing the brunt of reliability issues. In 1980, he comprehensively outperformed Scheckter as Ferrari fell behind. A year later, he did a similar job on Didier Pironi, and took two remarkable wins and a pole position in a deeply average car.

With Ferrari producing the best car in the field, 1982 was all set to be Gilles’ year – even after the furore of Imola, he was still the hot favourite to be champion, having outqualified Pironi in 12 of the 19 races they were partnered together prior to Zolder and usually outperformed him in races too. Despite the occasional error – like crashing out of the lead in Rio at the start of the season – he had developed into the complete driver, the one his colleagues looked to as the benchmark. There are very few drivers in racing history who reach that level and don’t achieve success with it – that’s why he has to be top of the list.